Catharsis

25 NOVEMBER 2021 - 22 FEBRUARY 2022, Eight Cubic Meters, Amsterdam, NLCatharsis presents a multidimensional body of work delving deeper into the symbol-making function of the psyche, growing into conscious from the unconscious, through painting as well as visual story-telling. The paintings along the sculptural elements, calligraphic symbols written on the windows and profound photographic imagery create an uncanny friction of diasporic culture-making and the inevitable search for roots, tongues and belonging. Together they emerge as carriers and creatures of Mongol Futurist semiotics and the chthonic realms of the Unconscious.

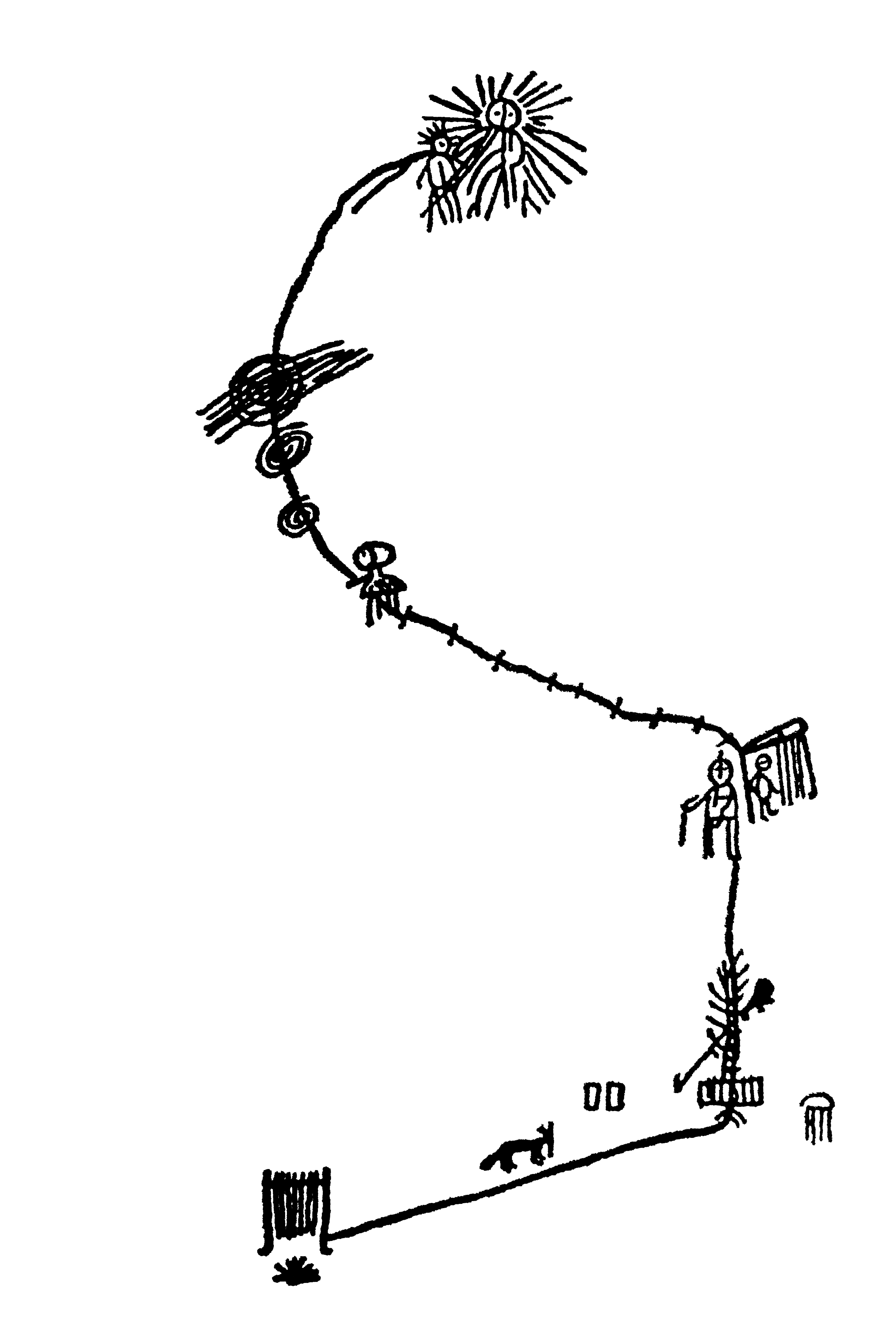

The Tamga

The Tamga of my grandfather. The word tamga literally translates to stamp: “As early as the first century A.D. tamgas appear among Sarmatian tribes north of the Black Sea as petroglyphs, carvings on gravestones, graffiti in tomb chambers, and marks on metal objects such as cauldrons, belt buckles, and bronze mirrors. The contexts indicate that they were symbols of magic power, signs of authority, and also marks of property comparable to family crests.’1 Tamga is a word of Turkic origin, ‘also witnessed in Mongol as tamga or temdeg,’2 and are mostly used in horse branding, indicating ownership.”3

1 Helmut Nickel, Tamgas and Runes, Magic Numbers and Magic Symbols, The Metropolitan Museum Journal, Volume 8, 1973, p.166

2 Niccolò Manassero, Tamgas, A Code of the Steppes. Identity Marksand Writing Among the Ancient Iranians, The Silk Road Journal, Vol. 11, 2013, p.69

3 Nomin Zezegmaa, The Shamanic Gaze—An Investigation into Mongol Futurist Ways of Being, 2020, p.122,

The Tamga of my grandfather. The word tamga literally translates to stamp: “As early as the first century A.D. tamgas appear among Sarmatian tribes north of the Black Sea as petroglyphs, carvings on gravestones, graffiti in tomb chambers, and marks on metal objects such as cauldrons, belt buckles, and bronze mirrors. The contexts indicate that they were symbols of magic power, signs of authority, and also marks of property comparable to family crests.’1 Tamga is a word of Turkic origin, ‘also witnessed in Mongol as tamga or temdeg,’2 and are mostly used in horse branding, indicating ownership.”3

1 Helmut Nickel, Tamgas and Runes, Magic Numbers and Magic Symbols, The Metropolitan Museum Journal, Volume 8, 1973, p.166

2 Niccolò Manassero, Tamgas, A Code of the Steppes. Identity Marksand Writing Among the Ancient Iranians, The Silk Road Journal, Vol. 11, 2013, p.69

3 Nomin Zezegmaa, The Shamanic Gaze—An Investigation into Mongol Futurist Ways of Being, 2020, p.122,

acrylics on cotton, 27,5 x 37,5cm, Mongolian silk frame.

The Psychic Nucleus

A cathartic and chimeric journey started with the four paintings, ‘The Psychic Egg’, ‘The Unfolding: Hiimori’, ‘Arcanum’, and ‘The Mirror of my Tongue, then the Tongue is the Soul.’ Conceptually inspired by the stream of thought of the Jungian analytical psychological approach, these four works were produced within an enormously dense and hermetic pace. Formally, however, they are directly informed by traditional Mongolian scroll painting. Thus, the focus of translation centers on the intricately sewn Silk frames that were a self-evident necessity for the Mongol nomadic lifestyle for efficient and easy mobility in contrast to frames and canvases of a more sedentary lifestyle.

The structure and make of the psyche proposed and outlined by C.G. Jung is the conceptual fundament of The Psychic Nucleus. The Egg itself is a loaded symbol of genesis and creation. It holds all psychic elements and capacity. Jung has named these shadow, anima and animus, and ego—all contained within the un/conscious in direct connection to the collective unconscious. The Psychic Nucleus is a speculative visual interpretation of the architecture of the psyche. Like a membrane or shell, the outermost layer is the collective unconscious. The fundamental transmitter between the depths of the individual unconscious to the conscious is dreams. The dreaming function of the psyche touches upon all psychic areas and elements embedded within the psychic nucleus, caressing and carrying information to the conscious from areas one is not aware of in the slightest. Dreams reveal to the conscious mind in symbolic vocabulary, poetically or brutally, the unreal and immaterial texture of the unconscious.

acrylics on cotton, Mongolian silk frame.

The Mirror of my Tongue, then the Tongue is the Soul shows the emergence of nine calligraphic symbols coming forth from the depths of the painting. It affords an engaged and curious gaze to grasp and see the symbols. These calligraphic symbols are shapeshifting between being letter or being drawing. With their enigmatic essence, they evoke an ambiguous reflection on the matter of language and writing. They are the result of a practice defined as Writing without writing. It has its origin in the speculative gesture of imagining the writing of Mongol bichig, the traditional vertical script of Mongolia, descendant from the 13th century Mongol Empire.

The ambiguous positionality of calligraphic symbols echoes a familiar equivocality. They resound a drifting between identities—a dancing between places, borders, and abilities. From a place of inability and not knowing, a practice of imagining and speculating came forth and manifested by constant repetition. The inability is specifically my inability to write in traditional Mongolian script. But precisely, from that place grew a language that reflects and resonates a diasporic dialect of writing: Writing without Writing. Calligraphic symbols—removed from the pressure of rationalized meaning, detached from the sticky rules of letters, language, and grammar—enact a language beyond language. One-dimensional logic does not stick to them.

The Mirror of my Tongue, then the Tongue is the Soul is an emulation of the sensation and sensibilities felt during the process and practice of Writing without Writing. The visual relation to Arcanum is thus by no means a coincidence: It is the chthonic pulsating origin of the calligraphic symbols, emerging from the depth of the visual enigma.

![]()

OS-HI: Object Study—Hermetic Investigation #1, 2020

paper maché, acrylic + spray paint, rice flour.

![]()

![]()

The Stone Sheep

black and white print on paper, A0

In search of a-linear history—connected to the collective narrative of the state—I tried to create a long-distance inventory of objects. Mainly, these objects were the objects of my grandfather. The outcome: My family in Mongolia sent me pictures of what remained of him. His deel, his hat, his belt, his pipe and tobacco utensils, his snuff bottle with the silken embroidered bag, his silver knife, a beautifully painted wooden chest, and the paw of a bear—the few objects that still connect us to him. Among the pictures of the various story-filled keepsakes, a stone caught my particular attention. This stone is an enormously precious heirloom of our family, nicknamed the sheep. Yet my family does not precisely know of its origin.

The Shaman and The Stone Sheep are low-quality phone pictures sent to me by my family in Mongolia to assist my endeavors. Regardless of whether they fully grasp my intentions or interests. However, the images function as a way of seeing and knowing I am unable to due to the distance.

Temporarily the spectator and I gain access to a faraway context and narrative. Momentary situations I would otherwise not be able to witness or encounter. My cousin—the shaman—the obscure figure embarking on a shamanic journey, or the stone that holds so much mystery and meaning to our family, are visual memories and remnants of moments I never witnessed myself.

![]()

![]()

The Unknown Song

steel, thread, synthetic hair, bells, ox bone.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Mirror of my Tongue, then the Tongue is the Soul shows the emergence of nine calligraphic symbols coming forth from the depths of the painting. It affords an engaged and curious gaze to grasp and see the symbols. These calligraphic symbols are shapeshifting between being letter or being drawing. With their enigmatic essence, they evoke an ambiguous reflection on the matter of language and writing. They are the result of a practice defined as Writing without writing. It has its origin in the speculative gesture of imagining the writing of Mongol bichig, the traditional vertical script of Mongolia, descendant from the 13th century Mongol Empire.

The ambiguous positionality of calligraphic symbols echoes a familiar equivocality. They resound a drifting between identities—a dancing between places, borders, and abilities. From a place of inability and not knowing, a practice of imagining and speculating came forth and manifested by constant repetition. The inability is specifically my inability to write in traditional Mongolian script. But precisely, from that place grew a language that reflects and resonates a diasporic dialect of writing: Writing without Writing. Calligraphic symbols—removed from the pressure of rationalized meaning, detached from the sticky rules of letters, language, and grammar—enact a language beyond language. One-dimensional logic does not stick to them.

The Mirror of my Tongue, then the Tongue is the Soul is an emulation of the sensation and sensibilities felt during the process and practice of Writing without Writing. The visual relation to Arcanum is thus by no means a coincidence: It is the chthonic pulsating origin of the calligraphic symbols, emerging from the depth of the visual enigma.

paper maché, acrylic + spray paint, rice flour.

OS-HI is a series of sculptural objects exploring transmutation, matter, and movement. The result of a dialogue, a balance of actio and reactio: they reflect on matter and tactility. As the title suggests, they contain a hermetic fragment of unknown origin and unrecognizable material qualities.

The Shaman

black and white print on paper, A0.

black and white print on paper, A0.

The Stone Sheep

black and white print on paper, A0

In search of a-linear history—connected to the collective narrative of the state—I tried to create a long-distance inventory of objects. Mainly, these objects were the objects of my grandfather. The outcome: My family in Mongolia sent me pictures of what remained of him. His deel, his hat, his belt, his pipe and tobacco utensils, his snuff bottle with the silken embroidered bag, his silver knife, a beautifully painted wooden chest, and the paw of a bear—the few objects that still connect us to him. Among the pictures of the various story-filled keepsakes, a stone caught my particular attention. This stone is an enormously precious heirloom of our family, nicknamed the sheep. Yet my family does not precisely know of its origin.

The Shaman and The Stone Sheep are low-quality phone pictures sent to me by my family in Mongolia to assist my endeavors. Regardless of whether they fully grasp my intentions or interests. However, the images function as a way of seeing and knowing I am unable to due to the distance.

Temporarily the spectator and I gain access to a faraway context and narrative. Momentary situations I would otherwise not be able to witness or encounter. My cousin—the shaman—the obscure figure embarking on a shamanic journey, or the stone that holds so much mystery and meaning to our family, are visual memories and remnants of moments I never witnessed myself.

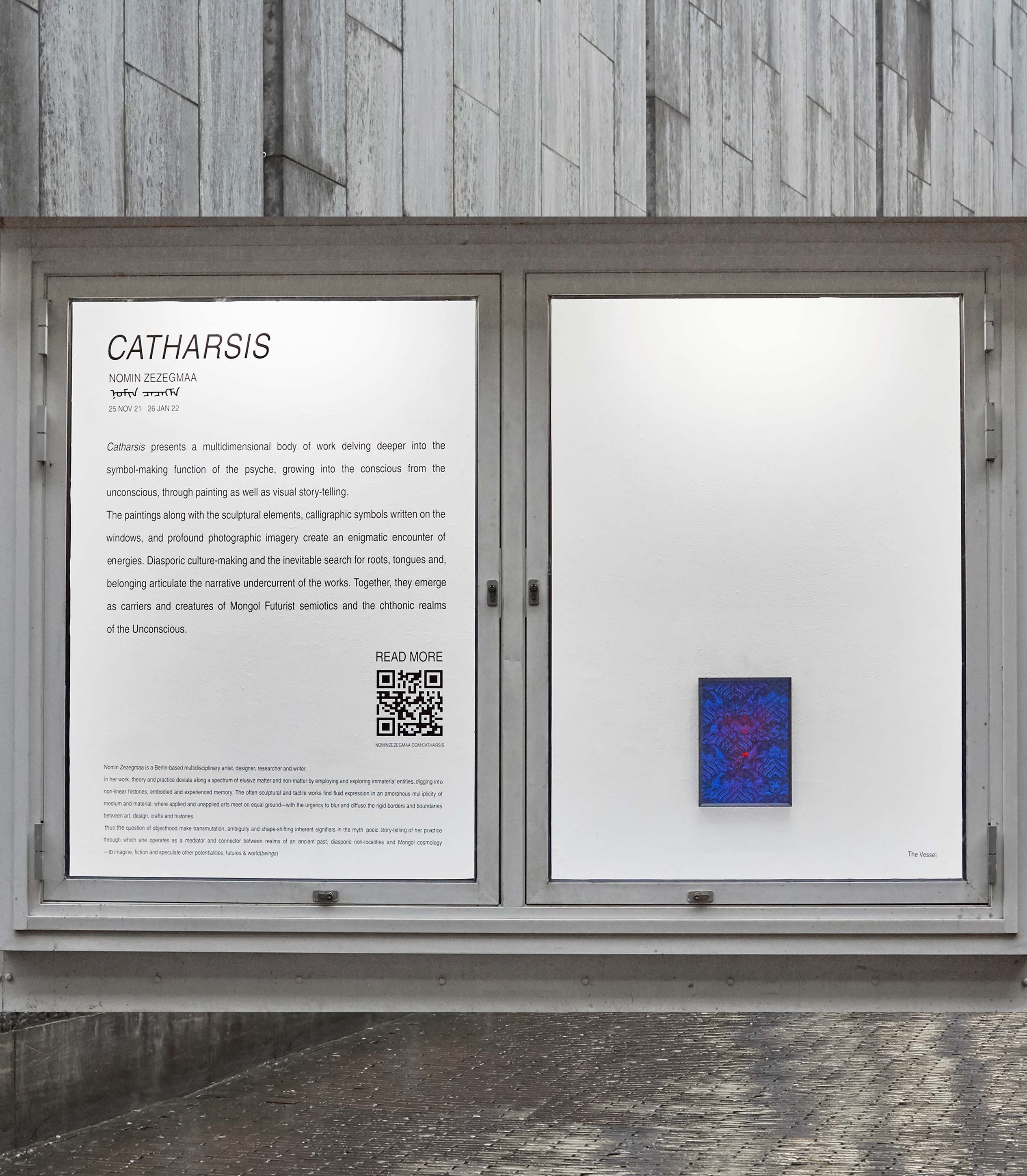

The Vessel

layered embroidered calligraphic symbols in red and black on Mongolian silk, 21 x 29,7 cm.

layered embroidered calligraphic symbols in red and black on Mongolian silk, 21 x 29,7 cm.

The Vessel is a rendition of the familiar embroidered Mongolian silk covers of previous book projects such as The Shamanic Gaze or The Red Book. The material and tactile quality of the intricate embroidery and silk together merge to become an autonomous visual piece. The embroideries require a close and attentive gaze to seek out the hidden: The black embroidery melts with the fabric, while the red embroidery radiates.

The Unknown Song

steel, thread, synthetic hair, bells, ox bone.

A song I’ve never known, the words I’ve never heard

Emotions surging, memories I’ve never had

Tears swelling, for the many forgotten

Caught in eternal limbo

Emotions surging, memories I’ve never had

Tears swelling, for the many forgotten

Caught in eternal limbo

Arcanum

acrylics on cotton, embroidered Mongolian silk frame.

![]()

The Ongon-hood

bells, lapis lazuli.

![]()

The Unfolding: Hiimori

acrylics on cotton, Mongolian silk frame.

acrylics on cotton, embroidered Mongolian silk frame.

Arcanum draws on the unknown almost chthonic depths, the dark and enigmatic layers of the unconscious. Painting layers of blue over and over, on white and black stains applied with paint-soaked cotton: The result is an abysmal depth of radiance, darkness, and richness of hues of blue that change through the affect of light.

The Ongon-hood

bells, lapis lazuli.

An ongon is an ‘interface where different worlds touch, such as in a shaman, a newborn, or a deceased person. Physical sites where spirit and earth touch, sacred sites like trees, mountains, or ovoos* are further manifestations of this occurrence. Linguistically the meaning of ongon sways between virgin or untouched. Further, it can be applied in the sense of something holy or sacred that should not be touched.’1

Ongon-hood defines an alternative object-hood that ascribes life or soul to objects rendered inert, dead, or inanimate. Strikingly, the paraphernalia and ritual objects used by shamans are called ongon. Temporarily inhabited vessels for the spirits of the shaman’s spirit helper family, they channel and manifest the shamanic power in the material reality.

1 Nomin Zezegmaa, The Shamanic Gaze, 2020, Chapter: The Shaman, The Ongon, p.89

*A stone cairn shrine for mountain spirits.

Ongon-hood defines an alternative object-hood that ascribes life or soul to objects rendered inert, dead, or inanimate. Strikingly, the paraphernalia and ritual objects used by shamans are called ongon. Temporarily inhabited vessels for the spirits of the shaman’s spirit helper family, they channel and manifest the shamanic power in the material reality.

1 Nomin Zezegmaa, The Shamanic Gaze, 2020, Chapter: The Shaman, The Ongon, p.89

*A stone cairn shrine for mountain spirits.

The Unfolding: Hiimori

acrylics on cotton, Mongolian silk frame.

The Unfolding: Hiimori articulates macrocosmic and microcosmic movement of energies. Hiimori is the Mongolian word for spirit, strength, and psychic energy. Symbolically often represented as the windhorse, it embodies the dynamic vehicle of one's life path.

exhibition documentation by Simon Pillaud

edited by Nomin Zezegmaa

edited by Nomin Zezegmaa