ӨРӨӨЛИЙН ХЭЛ БОЛ БАГАЖ,

ӨӨРИЙН ХЭЛ БОЛ АМЬ.

FOREIGN TONGUE IS A TOOL,

OUR OWN TONGUE IS THE SOUL.

“where the tongue should be,

only a black root”1

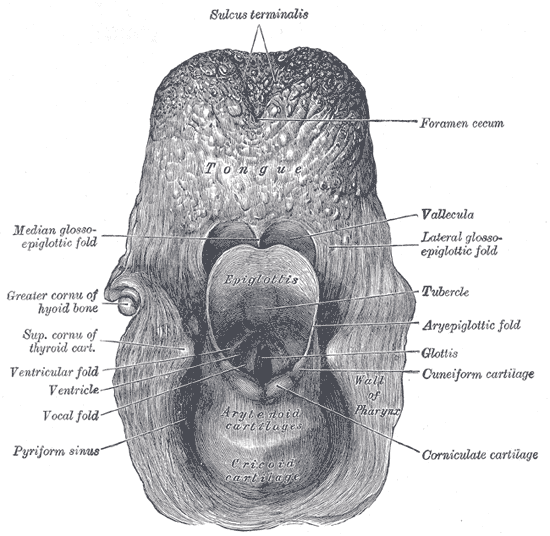

Imagine, someone is shoving something down your throat. Without your consent or approval. Obviously it does not go down well, no matter how stubbornly they keep on trying—they keep on pushing while you find yourself in terrifying agony, under tears, in excruciating pain—it feels alien, wrong and absurd. It is ripping the corners of your mouth. Your vocal cords are cracking, your eyes are shut in pain. Yet, the deepest wound is the invasive, invisible one inflicted on your soul.

How would you define the act of forcefully putting letters in one’s mouth, stuffing an alphabet down one’s throat, letters that are not only misplaced and discordant, but most of all letters that are unfit to neither accommodate the oral abundance of language as an alive entity, nor the constant dialectic flux and multiplicity of meaning? Flattening the rolling and twisting of the tongue, the vast hollow space of the mouth is constricted, the textures of syllables are lost alongside the oscillating resonance of vowels. Killing all oral diversity and ambiguity for the sake of ‘unification.’

Inevitably, it also becomes a question of design.

Inevitably, it also becomes a question of design.

THE TONGUE IS FIRST

Should my golden body weaken, so be it.

But my existing dynasty must not be broken.3

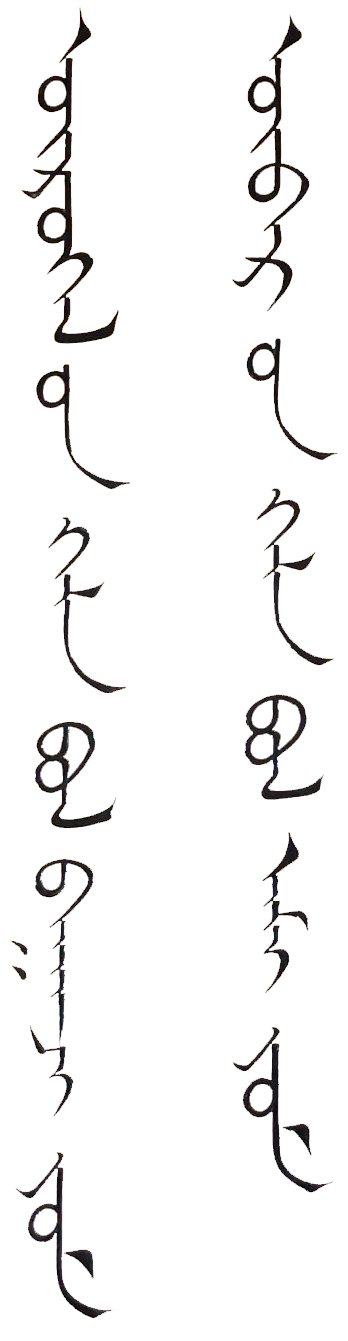

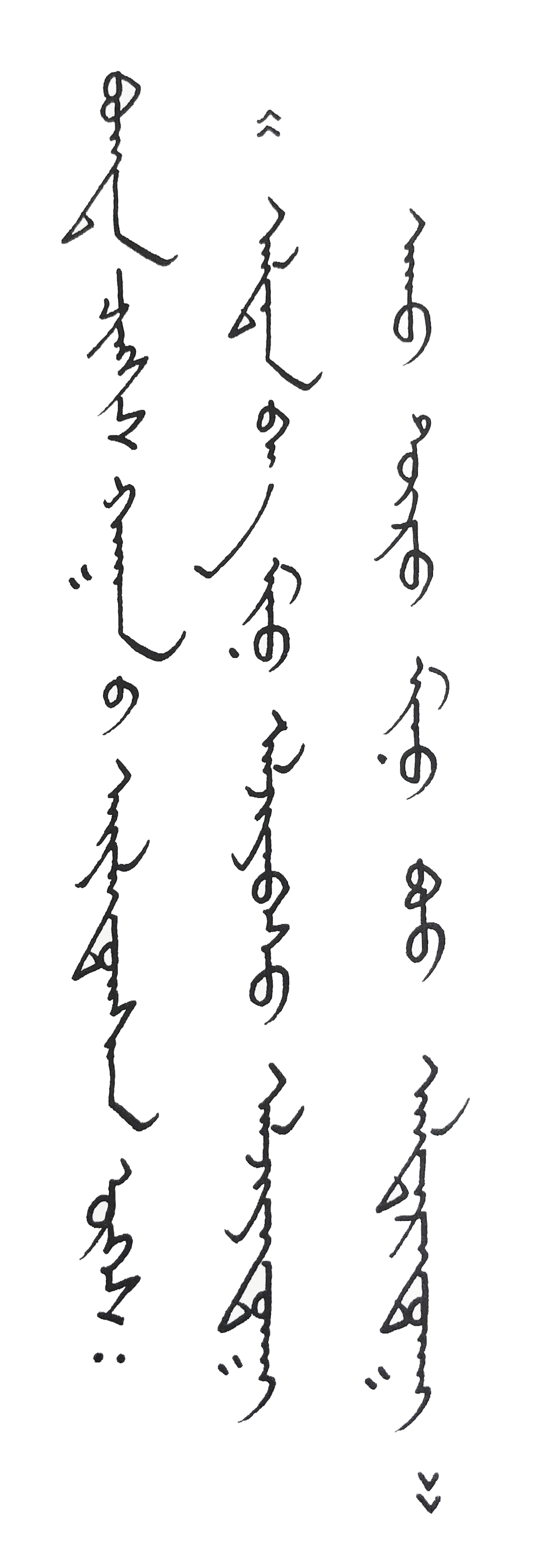

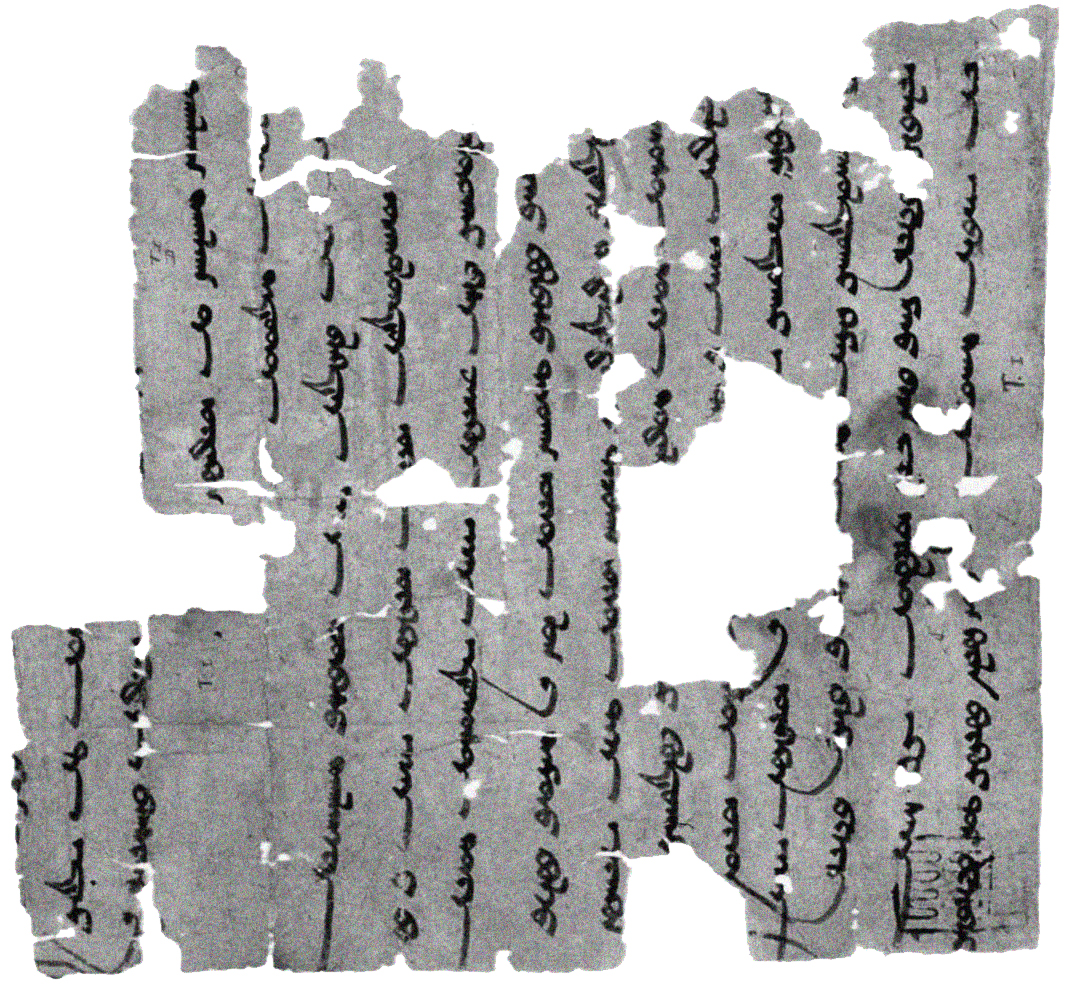

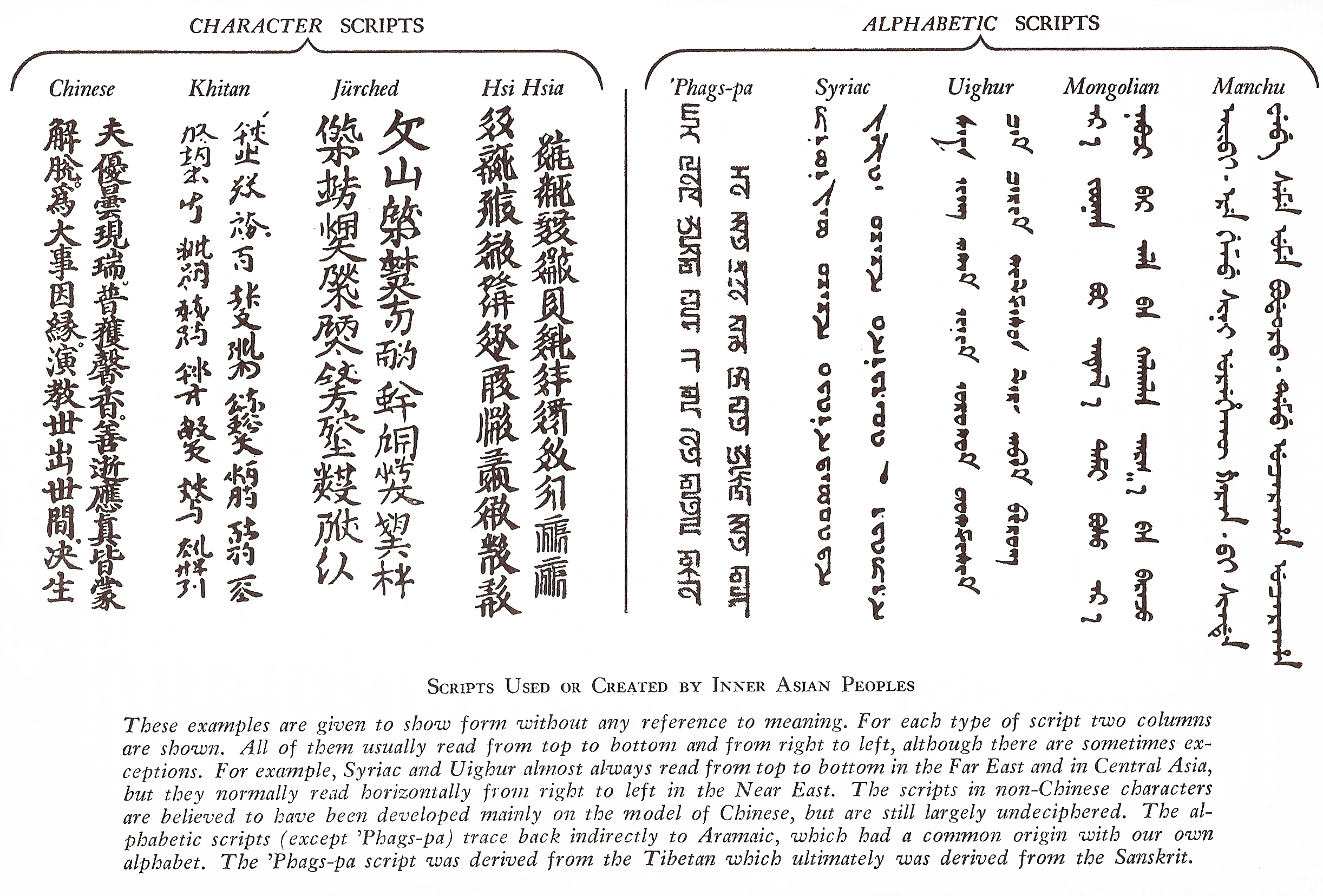

Mongol Bichig [ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ - Mongγol bičig] is a collective heritage that has endured throughout centuries to the present day and has been designed for the oral needs of many ethnic groups of the Greater Mongolian Nation. It is the last living legacy of Chinggis Khan, a writing system drawing on roots from Asia to Europe: In 1204, the Uyghur scholar Tata Tonga received the order from Chinggis Khan to create a hybrid script based on the Uyghur script adapted to the Mongol language.2

Uyghur was derived from the Sogdian alphabet, based on ancient Syriac and related to Aramaic as well as to Hebrew and Arabic, which were written from right to left. To further complicate things, the Uyghurs and Mongols turned the alphabet vertically, writing their sentences from top to bottom in the Chinese style.4

Sogdian/Uyghur/Mongol

from East Asia. The Great Tradition, 1969, 257

Inherently it is a writing system that adapts itself to the tongue, and not vice versa. Its own unique laws adhere to oral harmony and balance.5 Comparable to a musical score, it truly represents a form of embodied scripture, thus being the only writing system that is fully capable to embrace the wide variety of dialectic differences present in the manifold Mongolic ethnic groups and their tongues. Just like Mongol culture and identities, the Mongol language has faced externally-induced suppression on several occasions throughout history, and history repeats itself again in the 21st century, this time around with another assailant encroaching from the South.

BROKEN TONGUES,

RIPPED OUT TONGUES

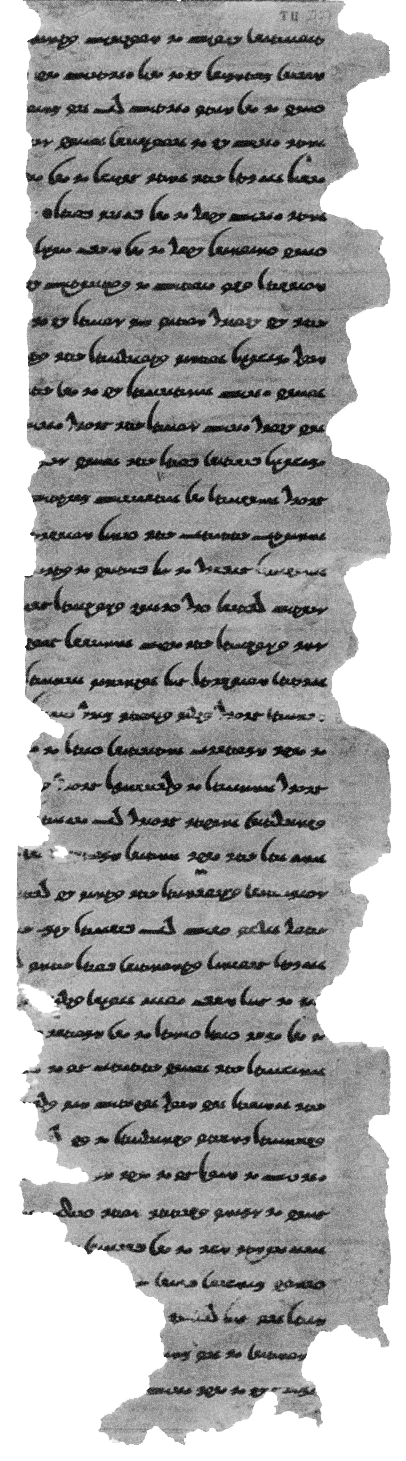

In what is known to most as the Republic of Mongolia, during the 1940s the Cyrillic alphabet6 was ‘introduced’ as part of a Soviet socialist regime during Stalin's Great Purge, molding Mongolia into a satellite state. However, in reality, it became a blood-soaked colony7, its culture crushed, its people left with collective memories of heritage, identity and tradition drowned in a pool of forced forgetting.8

Mongolia suffered “decades of suppression under state socialism, coupled with Soviet domination (1921-1989)”9 that aimed to erase and suppress all religious practices: “Mongolia’s political cleansing began in the late 1920s and peaked in 1937-1940”10 as part of the Stalinist state purges.

The Socialist state labeled the Buddhist clergy, the intelligentsia, the upper class, the wealthy nomads, and the Buryats enemies of the people and began prosecuting them. Sources give the number of those killed as being between 50.000 and 100.000 in a country with a population of less than 800.000 at the time. The exact figure will probably never be known, because many records of the period were lost or destroyed. The state also destroyed material objects related to the people it purged and exterminated, among them eight hundred Buddhist monasteries with their libraries, religious objects and artworks.11

The brutal persecution of shamanism, the fundamental preserver and transmitter of intergenerational knowledge and tradition of the Mongols,12 in conjunction with the molding of Cyrillic onto Mongol tongues, were systematic tools of oppression and ethnic cleansing: “State socialism implemented some brutal measures to ensure forgetting, homogenizing and control of knowledge throughout the country.”13

State-enforced forgetting was a systematic and continuous process that extended far beyond the initial destruction and killing. In order to erase memories of its own violence, the state […] buried purge victims in unmarked mass graves, closed and controlled archives, and silenced individual stories. The new memories and remembering practices it created were meant to distract from, override, and substitute for actual memories. Many of them took the form of grand public rituals designed to compel acceptance of the state’s narrative as unquestioned truth.14

The collective pain of forced forgetting is utterly complex and undeniably its grasp reaches across generations, time and space. When what Rob Nixon innovatively defines as slow-violence15 coalesces with the additional layer of deep-time proposed by the anthropologist Richard D.G. Irvine, the outcome is the idea of slow-violence in deep-time16: a violence that is exerted in the present, within the human domain just as within the environmental. Its consequences fan out across deep-time into the aeon of amnesia. It goes beyond any of our generational lifetimes, and perhaps even transcends our linear, disconnected understanding of time—a violence whose consequences we cannot even fathom, exerted on bodies of earth, bodies of water and bodies of beastly as well as human flesh—it is a feigned blindness to the future, for which we need to be accountable, aware and responsible in the here and now.

When the forced forgetting of one's cultural heritage is set in motion by external violence, by an external aggressor with subversive strategic aims of solidifying their historical and political narratives and motives—by the insidious intergenerational erasure of sublime signifiers of identities—often being the way of life, and language—it is a form of invisible and intimate violence. It may only take a few generations to ‘bear fruit’ but it might also lead to absolute extinction. It forcefully creates artificial mutations in the minds, mouths and bodies of diaspora and descendants remaining in the homeland alike.

Not only have Mongolians suffered under Soviet domination, indigenous peoples like the Buryats, Tuva and Kalymks have met the same fate. The Greater Mongolian Nation enveloped territories where the indigenous population is largely Mongolic. A large part of these territories have been swallowed and claimed by Russia, their indigenous populations now degraded to the status of ‘ethnic minorities’. Their native languages are critically endangered, however most are fluent in Russian. Cyrillic ever-present, their native tongues, too, are caught in oppressive oblivion and on the cusp of extinction.

In a poem written by the artist Natalia Papaeva who grew up in post-Soviet Buryatia, this feeling of voicelessness is given a voice:

When the forced forgetting of one's cultural heritage is set in motion by external violence, by an external aggressor with subversive strategic aims of solidifying their historical and political narratives and motives—by the insidious intergenerational erasure of sublime signifiers of identities—often being the way of life, and language—it is a form of invisible and intimate violence. It may only take a few generations to ‘bear fruit’ but it might also lead to absolute extinction. It forcefully creates artificial mutations in the minds, mouths and bodies of diaspora and descendants remaining in the homeland alike.

Not only have Mongolians suffered under Soviet domination, indigenous peoples like the Buryats, Tuva and Kalymks have met the same fate. The Greater Mongolian Nation enveloped territories where the indigenous population is largely Mongolic. A large part of these territories have been swallowed and claimed by Russia, their indigenous populations now degraded to the status of ‘ethnic minorities’. Their native languages are critically endangered, however most are fluent in Russian. Cyrillic ever-present, their native tongues, too, are caught in oppressive oblivion and on the cusp of extinction.

In a poem written by the artist Natalia Papaeva who grew up in post-Soviet Buryatia, this feeling of voicelessness is given a voice:

A shaman told me once,

I lost my soul

My soul left my body

Now I am an empty hole

The tongue has burned

My mouth is full of ashes

I turned into a werewolf

Unable to pronounce my grandmother’s name

Howling with a foreign accent.17

I lost my soul

My soul left my body

Now I am an empty hole

The tongue has burned

My mouth is full of ashes

I turned into a werewolf

Unable to pronounce my grandmother’s name

Howling with a foreign accent.17

As socialism continued, each generation thought of the previous one as having endured a more oppressive regime than they themselves were experiencing. The 1930s are known as a time of arrests, fear and suspicion, when ‘one had to be afraid of one’s shadow’. It was the time of the worst oppression, and memories of it are murky at best. It is possible the technologies of forgetting became less obvious and less coercive, or that individuals became desensitized. At the same time, each generation thought of themselves as knowing less than the others. [...] Despite all these differences in remembering and forgetting, the anxiety about the loss of the past and a profound uncertainty about the newly discovered past spans all generations to differing degrees.18

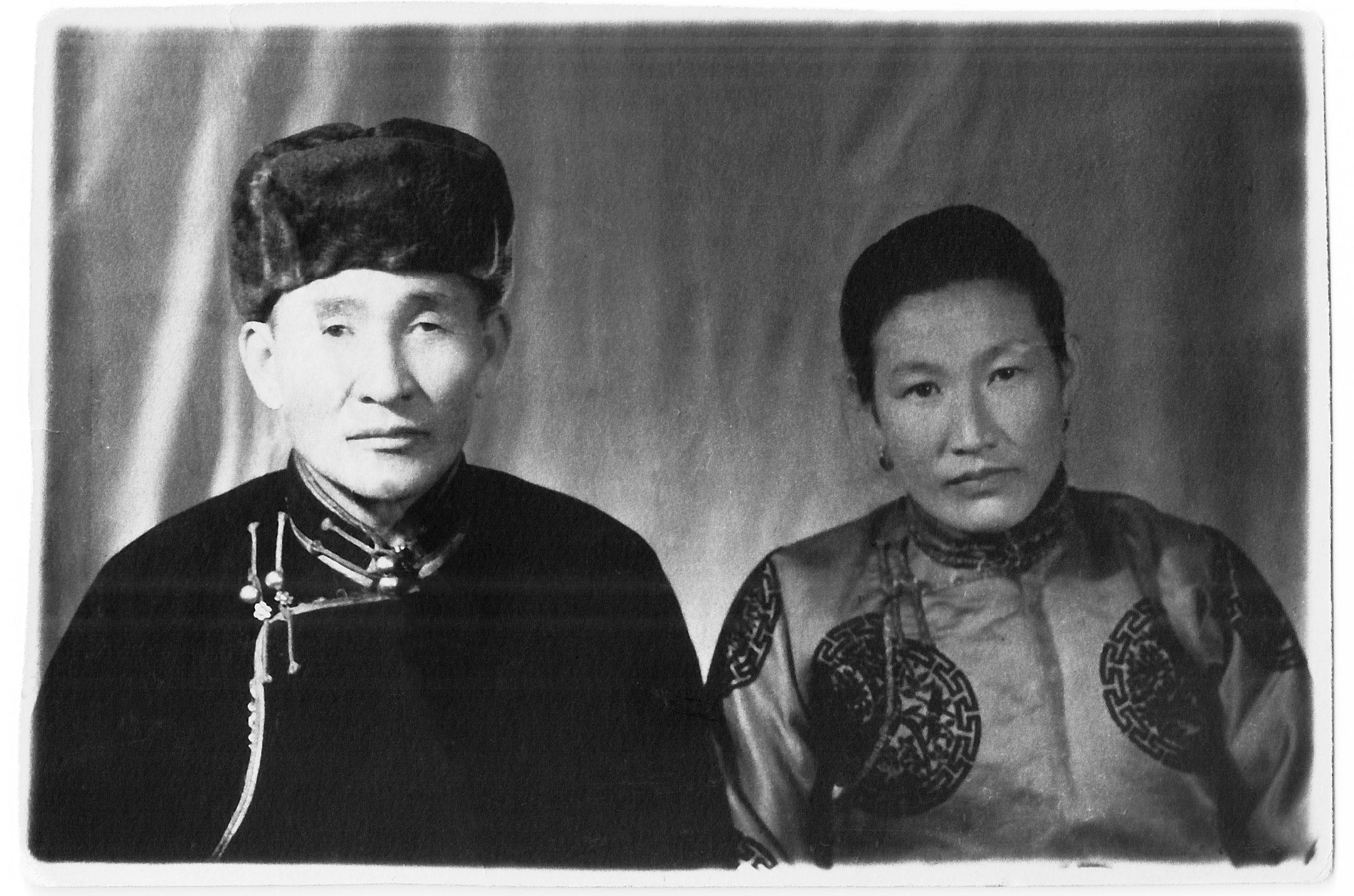

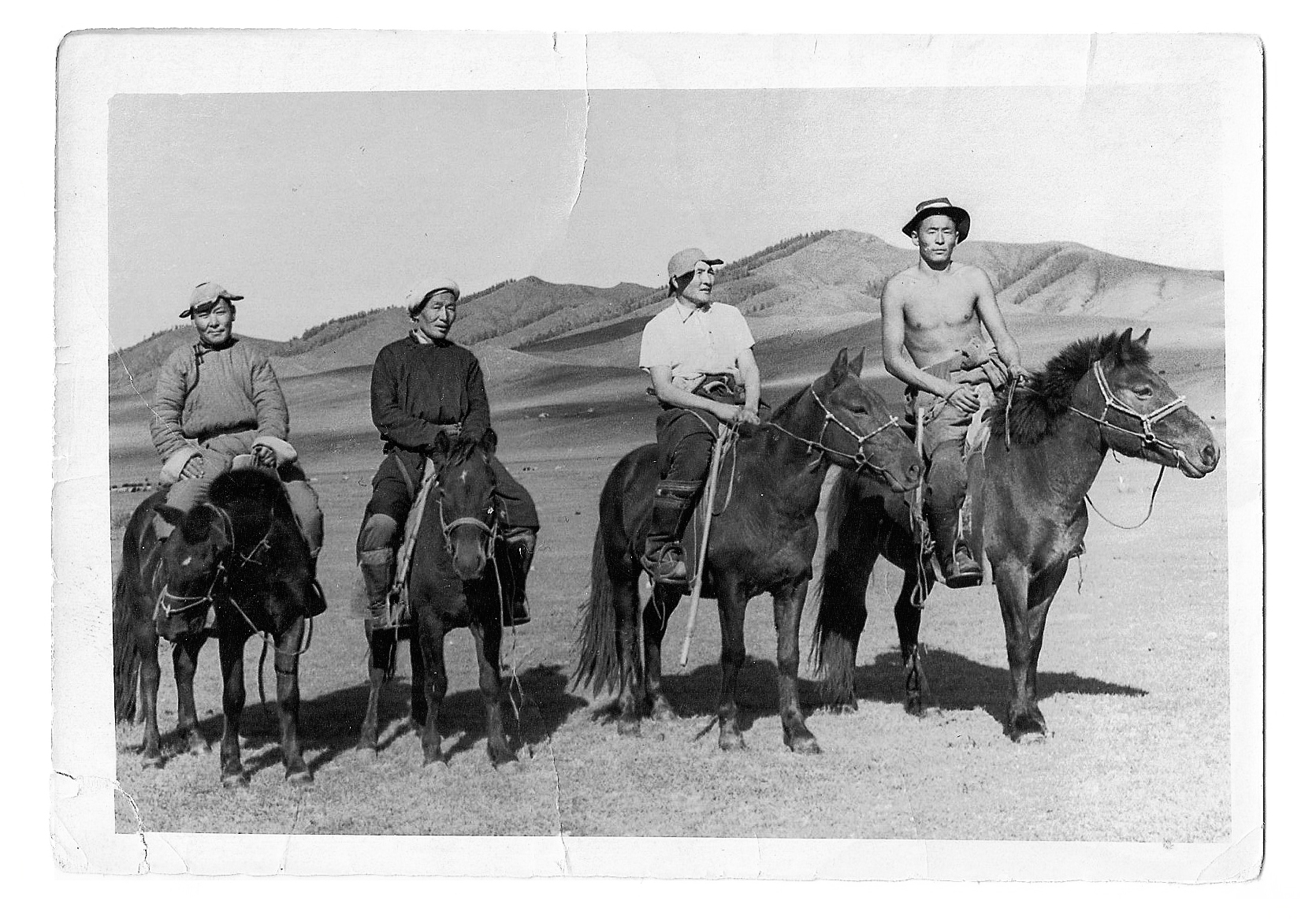

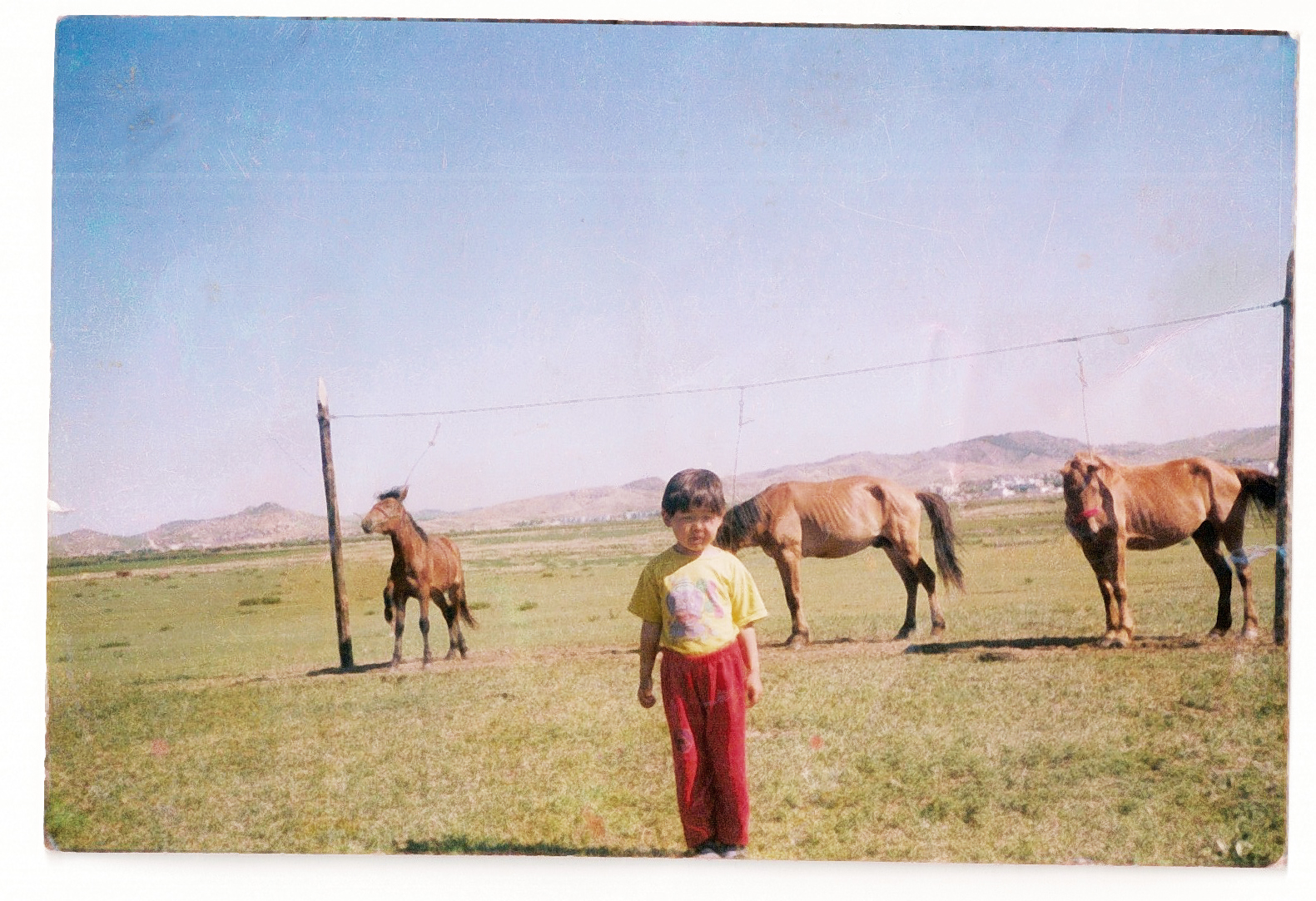

I barely remember or know much about my grandfather, let alone my grandmother, aside from handed down memories, oral accounts and old photographs. These are the most valuable and priceless fragments I can receive, collect and hopefully preserve. My grandfather’s homeland is present in our family’s genealogy, yet I do not have the slightest clue of the homeland of my great-grandfather, let alone my great-grandmother. The more recent family history belongs to the realm of memories of my mother and her siblings.

From the Mongolian central grasslands I can trace my grandfather’s steps to the Northern mountainous regions of Selenge close to the Russian border, but beyond his realities and lifetime, to my great-grandparents, or even further than that, we simply do not know and may never learn. For their traces are fragmented and scattered across our ancestral lands. Our memories are caught in limbo, pieces are erased or missing—rendered as indecipherable matter—vague and shapeless.

The involuntary disconnectedness from our past is intergenerational, invisible and insidious. We are a generation, diaspora or not, that barely remember anything beyond our recent graspable collective genealogical history:

The involuntary disconnectedness from our past is intergenerational, invisible and insidious. We are a generation, diaspora or not, that barely remember anything beyond our recent graspable collective genealogical history:

One of the state projects for making a complete break with the past was to destroy or confiscate families’ genealogical records; another was to force people to drop their family name and adopt their father’s patronymic instead (the mother’s name if the child was born out of wedlock).19

Adding to generations of state-induced silenced and suppressed voices, the diasporic movement of Mongols in the 20th century has inevitably added to unintentional disconnectedness: My parents met in then-GDR Berlin, my father a graduate of the TU Dresden and my mother in the midst of her studies in Forst, Lausitz. Fast forward, I was born here, and raised here. Yet, luckily I grew up with a very close relationship to the land of my origin and culture as I got to travel and visit Mongolia from an early age on. A fundamentally important aspect of my times in Mongolia was spending time with the part of my family who has continued to this day to lead a semi-nomadic life. Through them, I was exposed to and became part of a completely different reality, even if only for the duration of the summer months. In my youth these months meant pure bliss.

It is the country of my ancestors, soaked with a vast history that is mirrored, though blurry, within my own body and existence. It is the country where the bones of my grand-mothers have been buried, along with the bones of the culture I am tirelessly digging out of the weeping soil of Mother Earth. I did not grow up completely isolated and distanced from its culture and tradition, as I used to spend summers in Mongolia from a very young age. Thus its language, customs and traditions were not altogether detached or foreign to me. However, in terms of my identity and belonging there may have always been a slight undefined void. A sense of veiled being, an in-between being, an internalized feeling of not being enough.

The history of Mongolia, its political violence and neoliberal capitalist democracy were realities completely detached from the blissful childhood memories I collected during these visits, but ever so much make sense now. It is now that I can clearly see how the genealogical narratives of my grandfather, my mother and my family as a whole were held within the palm of much greater forces. This chain of state-controlled dynamics that took hold of a whole generation of diaspora Mongolians is fascinating, yet not spoken about or perhaps not actively, consciously thought of. I mean, who would sit down and cross-examine their life story with that of their father and their father’s father — and with the dynamics of the state?20

Regardless of my relatively

good verbal skills in Mongolian, there has always been a deep-seated bitter sweet taste of uncertainty and insecurity in terms of language. Indeed, I was raised bilingual, but the amount of Mongolian we spoke at home, or the amount of Mongolian I picked up and perhaps solidified in, on, under or around my tongue during my summer months never seemed enough. The lack of the most mundane exposure to solidify the tongue to write and read, meant that I could never achieve mental or written fluency in Cyrillic Mongolian, let alone classical Mongol.

The pain of not knowing my own mother tongue in its true and authentic richness, not knowing how to write my mother’s name in true and proper Mongol bichig—a pain that could be described as a dark void, an obscure figure entering the gates of my consciousness—follows me like a shadow. There is a fragment of myself that I may never find. It is always there, this spectre of inner oppression. This pain envelops generations and geographies: my personal reality inarguably stems from diasporic movement,21 not to blame it, but to humbly acknowledge and locate my inability of writing, reading and speaking true classical Mongol.

The pain of one’s inability to express, shout, sing, scream and even think or dream in one’s own tongue goes beyond histories and bodies, beyond the domain of language and man-made borders. And still, somewhere, these realities are being forced to repeat itself.

The pain of not knowing my own mother tongue in its true and authentic richness, not knowing how to write my mother’s name in true and proper Mongol bichig—a pain that could be described as a dark void, an obscure figure entering the gates of my consciousness—follows me like a shadow. There is a fragment of myself that I may never find. It is always there, this spectre of inner oppression. This pain envelops generations and geographies: my personal reality inarguably stems from diasporic movement,21 not to blame it, but to humbly acknowledge and locate my inability of writing, reading and speaking true classical Mongol.

The pain of one’s inability to express, shout, sing, scream and even think or dream in one’s own tongue goes beyond histories and bodies, beyond the domain of language and man-made borders. And still, somewhere, these realities are being forced to repeat itself.

The word Mongol in various contemporary and historical scripts:

1. traditional, 2. folded, 3. 'Phags-pa, 4. Todo, 5. Manchu, 6. Soyombo, 7. horizontal square, 8. Cyrillic

SOUTH OF THE DESERT,

NORTH OF THE WALL

This somewhere is Southern Mongolia, widely and wrongly known as ‘Inner Mongolia’, Autonomous Region, or province of China—this terminology itself is an act of territorial propaganda: for the gaze that differentiates between the two Mongolian territories as ‘Outer’ and ‘Inner’ presumes a Sino-centric position. In the Mongolian language, the appropriate terms are Uvur and Ar, Southern and Northern.22

The history of modern Southern Mongolia reveals a process of fragmentation of integral territory through invasion, politically motivated mass killings, and the eradication of the traditional nomadic economy. While the colonizers were the Chinese (Han people) and the Japanese, the genocide was carried out by China alone.23

The historical background of how two separated Mongolias came into existence reaches all the way back to the Qing dynasty24 and its collapse, though it was the insidious political as well as territorial intentions and claims of their neighbours that solidified these man-made borders and thwarted the reunification of Greater Mongolia.

With the fall of the Qing dynasty after a three century long reign, Northern Mongolia declared its independence in 1911 and the Bogd Khaganate was founded,25 which found exuberant resonance among the Mongolians living south of the Gobi Desert. However, their earnest attempts for unification were heavily blocked by “the Chinese warlords, the successors of the Jindandao,26 [that] had built up substantial bases in the Southern Mongolian grasslands, and squashed the Mongolian attempt for independence with brute force.” As a result, “Southern Mongolians were left in an uneasy coexistence with their Chinese colonizers.”27

Northern Mongolia’s declaration of independence became technically void with the 1915 Treaty of Kyakhta between Russia, Mongolia and China that denied full autonomous independence of Mongolia and acknowledged Chinese suzerainty, with Southern Mongolia staying under full Chinese control. It was in 1945 with the Yalta Conference that the irreversible separation and fate of both Mongolian nations was decided as the “Soviet Union believed a merger between Southern and Northern Mongolia would possibly provoke nationalism among the Buryat Mongolians of Siberia, who would then join the merger. The Soviet Union did not welcome the potential emergence of a Greater Mongolia at all.”28

It is through maps and terminology that China tries to solidify political and historical narratives to justify territorial claim to what was under former Qing rule, within which, ironically, China itself was only a province.

The vast grasslands of Southern Mongolia became the central stage for “an extravagant display of power, wealth and military resolve”29 during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, in which a massive genocide campaign against Southern Mongolians took place, purging intellectuals, and framing nomadic herders as the ‘exploiting class’.

It is through maps and terminology that China tries to solidify political and historical narratives to justify territorial claim to what was under former Qing rule, within which, ironically, China itself was only a province.

The vast grasslands of Southern Mongolia became the central stage for “an extravagant display of power, wealth and military resolve”29 during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, in which a massive genocide campaign against Southern Mongolians took place, purging intellectuals, and framing nomadic herders as the ‘exploiting class’.

The exuberance is starkly juxtaposed with the reality of Southern Mongolia, that an independent nation can be reduced to an occupied land, a sovereign people can be downgraded to an ‘ethnic group’, a vast and beautiful territory can be turned into a mining pit, a vibrant culture can be trivialized to a window display within a matter of decades. China reminds us that this kind of social and cultural devastation is possible with a government committed to aggressive territorial annexation and cruel colonial policy. It can

be accelerated if you throw in a massive genocide, population transfers, cultural eradication, economic exploitation and environmental destruction. Southern Mongolia today is sad testament to a Chinese Communist edict that change comes from the barrel of a gun.30

Tragically, the campaign of physical as well as cultural genocide, ethnic assimiliation and eradication of Mongol identity has never concluded with the Cultural Revolution and has taken on many different faces.

What had started out as territorial greed and claim with military, politically motivated intentions, land for opium planting or farming, has grossly mutated into absolute exploitation of natural resources: Southern Mongolia is one of the most abundant natural resources for coal, copper, oils, gases and especially rare earth.31

Under the term ‘ecological migration,’32 a enforced resettlement of the pastoralist nomads has been implemented since the early 2000s, criminalizing the keeping of live-stock and essentially putting all blame for the desertification of the grasslands on the nomads, who ironically have lived on these exact lands since since generations, when in reality the majority of the environmental issues are caused by the intensive, state-supported migration of Chinese settlers and farmers.33

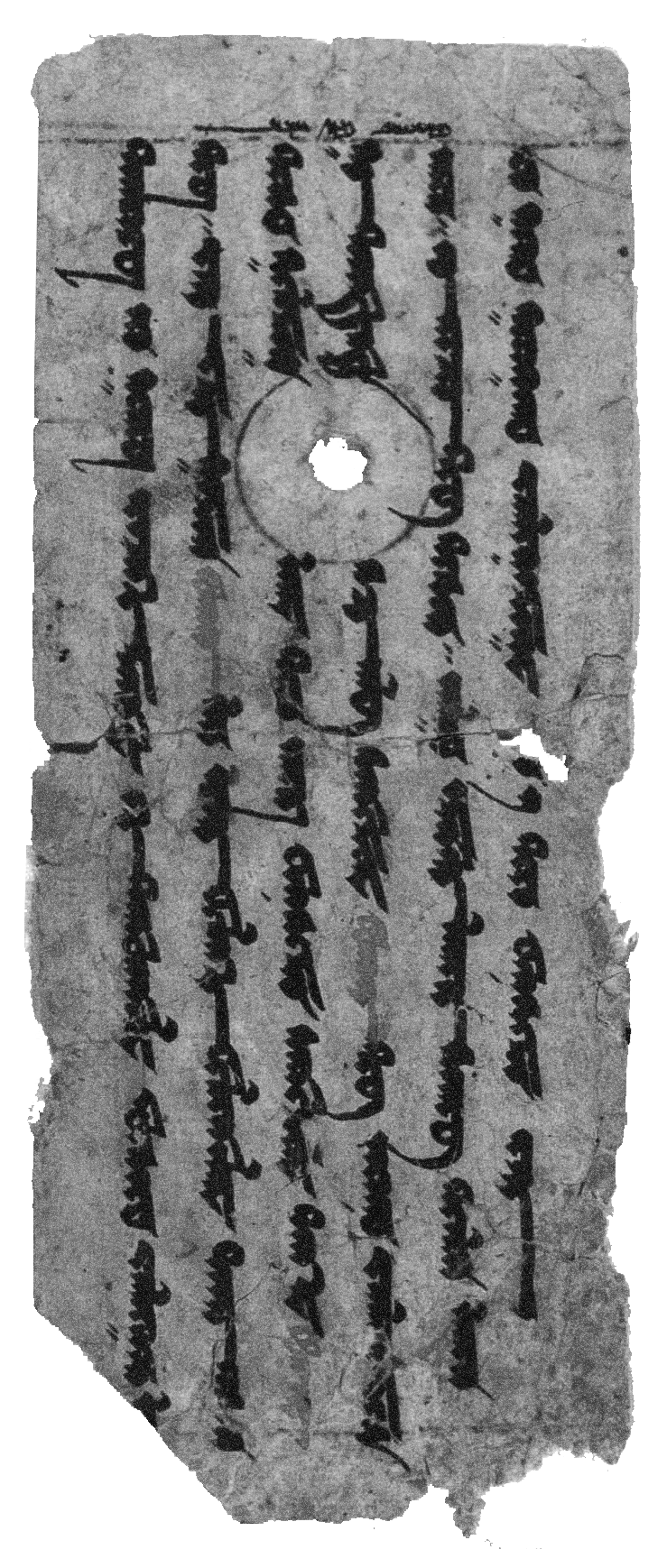

Upon the context of forcefully removing Mongol nomads from their own ancestral lands, removing them from their traditional way of life, thus prohibiting their essence and being, or if you will, the practice of their identity and culture. The last sanctuary left to the Mongols south of the Gobi, was their language and our collective heritage, the classical Mongol script.

What had started out as territorial greed and claim with military, politically motivated intentions, land for opium planting or farming, has grossly mutated into absolute exploitation of natural resources: Southern Mongolia is one of the most abundant natural resources for coal, copper, oils, gases and especially rare earth.31

Under the term ‘ecological migration,’32 a enforced resettlement of the pastoralist nomads has been implemented since the early 2000s, criminalizing the keeping of live-stock and essentially putting all blame for the desertification of the grasslands on the nomads, who ironically have lived on these exact lands since since generations, when in reality the majority of the environmental issues are caused by the intensive, state-supported migration of Chinese settlers and farmers.33

Upon the context of forcefully removing Mongol nomads from their own ancestral lands, removing them from their traditional way of life, thus prohibiting their essence and being, or if you will, the practice of their identity and culture. The last sanctuary left to the Mongols south of the Gobi, was their language and our collective heritage, the classical Mongol script.

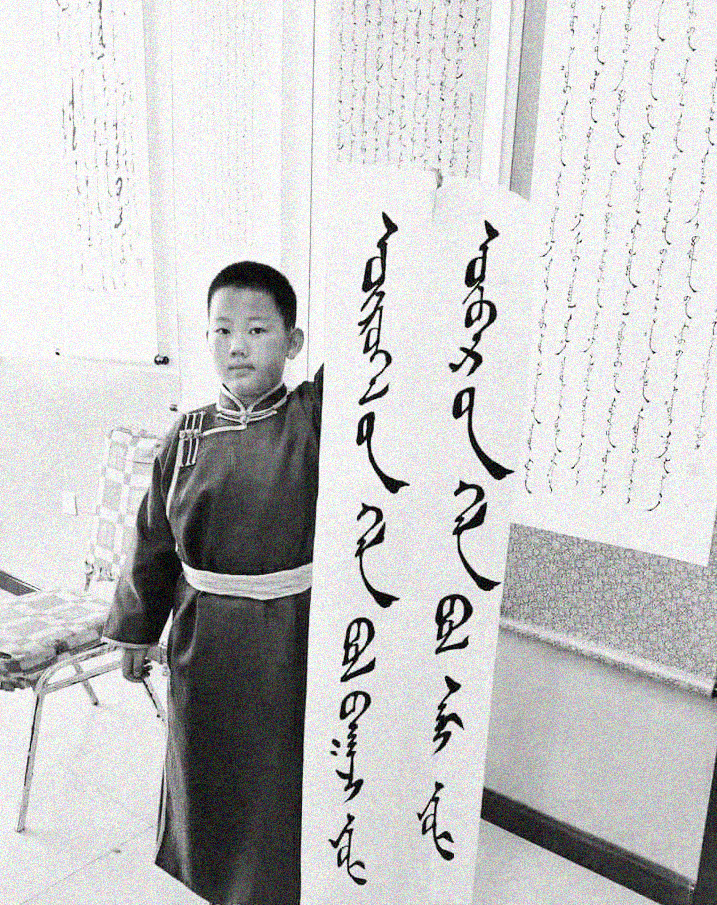

A young Southern Mongol student protesting:

“Ureeliin hel bol bagaj, uuriin hel bol ami”

FOREIGN TONGUE IS A TOOL,

OWN TONGUE IS THE SOUL

In the same modus operandi, the central Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party launched the so-called ‘second generation bi-lingual education’ policy in September 2020 changing the language of instruction at schools from Mongol to Mandarin. This has caused global as well as local uproar and protests among Mongols, however with an inarguable underrepresentation of Mongolian voices in media, this very urgent matter found little resonance or visibility outside of Mongolian social media platforms. Dismantling what is dressed up as a progressive policy of sorts, in fact is neo-colonial oppression that aims for absolute sinification and homogenization of its ‘minorities.’

Prohibiting and forcing assimilation by way of restriciting the tongues of Southern Mongolians is cultural genocide. It is inherently a systematic, slow-violent erasure of the Mongolian language, by forcefully removing ethnic Mongolians from their traditional nomadic way of life, ancestral lands and a forceful disconnectedness intergenerationally. The language policy is an immediate attack and attempt of obliterating Mongol identity. This strategy has far reaching historical roots stemming directly from the cultural as well as physical genocide in Southern Mongolia during the Cultural Revolution, building squarely upon the more ‘recent’ territorial issues of mining and exploiting the rich natural resources, this conflict mirrors strangely familiar environmental issues in Northern Mongolia.

Chinese-occupied Southern Mongolia is the only place on earth where a cohesive, dense population of ethnic Mongolians live in a geographic territory that is almost the size of the country of Mongolia, where this legitimate, authentic written and spoken language is still alive—the most precious cradle of a language and writing system that descends from the era of the Mongol World Empire of Chinggis Khan and our forgotten ancestors.

Banning the free, and rightful use of one’s mother tongue—the free, and rightful expression of one’s culture and heritage, which this very language and script embodies—is like breaking the essence, the spirit, the soul of a people. Chopping away at their limbs, ripping out the tongues of an entire generation who live on their ancestral lands.

The frustration, fury and anger of our ancestors living through us today, I try to bring to light, the dark pain, the wound inflicted on generations before us: the embodied intergenerational trauma of forced forgetting of our language and script that once formed the link to our collective past, buried through carefully orchestrated destruction. The exact same history being repeated, the exact same atrocious disconnectedness of forced forgetting being bound upon an entire generation of young Mongols is utterly excruciating and unacceptable.

Imagine, you cannot speak to your grandparents, spell their names, as your tongue cannot follow the highs and lows of the vast ranges of vowels and vocals, as mountains stretch across the horizon. Imagine, you cannot sing songs of praise in your mother tongue to express the beauty of those mountains in front of you. Imagine, you cannot access your own culture’s history, in your own language.

Cutting the tongue out is cutting the roots off, cutting the tongue out is severing you from your family, identity, culture and homeland. Without your tongue, something will feel forever lost. In the dark web of the unconscious, the dark place our memories of our ancestors are being forgotten, or waiting to be remembered again.

My own reality is testament to this deeply agonizing void, artificially created through generations of state-induced slow-violence overlapping with diasporic spheres of a multitude of narratives. I cannot speak to my ancestors, for I do not speak their tongue, and scarcely pick up a syllable or two that hint at a word that I barely may grasp. Our tongues are different, our mouths are incongruent. And I cannot avoid to wonder if it would be any different, if history would have not been so terrifyingly violent to our great-great-great-grandparents throughout the 20th century, the consequences still slowly, slowly simmering and surfacing. What would our homeland be like? What would our tongues and minds be like? Our tongues are becoming ghosts of what once was.

Inescapably, the brutal reality and (non)relationality to our collective heritage, Mongol bichig, written and oral, may still be in a deep slumber of the psyche somewhere. And as painful it may be to confront the violence-soaked history of Northern and Southern Mongolia, I believe it to be inevitable, in fact an imperative to reach a sustainable understanding not only for the future of our culture and people, but to also reclaim our collective heritage and history. If forgetting is a process, then remembering is as well. As tragic as it may be, in honour of our ancestors and the many Mongols that lost their lives and still are, I wish we can articulate resilience in response,34 once our eyes, minds and mouths open to the past and the very urgent present. May our tongues find the tones, high and low as the mountains and valleys of Mongolia. May our mouths find the flow of the rivers and trace the vastness of the steppe in our throats and lungs—and breathe.

Prohibiting and forcing assimilation by way of restriciting the tongues of Southern Mongolians is cultural genocide. It is inherently a systematic, slow-violent erasure of the Mongolian language, by forcefully removing ethnic Mongolians from their traditional nomadic way of life, ancestral lands and a forceful disconnectedness intergenerationally. The language policy is an immediate attack and attempt of obliterating Mongol identity. This strategy has far reaching historical roots stemming directly from the cultural as well as physical genocide in Southern Mongolia during the Cultural Revolution, building squarely upon the more ‘recent’ territorial issues of mining and exploiting the rich natural resources, this conflict mirrors strangely familiar environmental issues in Northern Mongolia.

Chinese-occupied Southern Mongolia is the only place on earth where a cohesive, dense population of ethnic Mongolians live in a geographic territory that is almost the size of the country of Mongolia, where this legitimate, authentic written and spoken language is still alive—the most precious cradle of a language and writing system that descends from the era of the Mongol World Empire of Chinggis Khan and our forgotten ancestors.

Banning the free, and rightful use of one’s mother tongue—the free, and rightful expression of one’s culture and heritage, which this very language and script embodies—is like breaking the essence, the spirit, the soul of a people. Chopping away at their limbs, ripping out the tongues of an entire generation who live on their ancestral lands.

The frustration, fury and anger of our ancestors living through us today, I try to bring to light, the dark pain, the wound inflicted on generations before us: the embodied intergenerational trauma of forced forgetting of our language and script that once formed the link to our collective past, buried through carefully orchestrated destruction. The exact same history being repeated, the exact same atrocious disconnectedness of forced forgetting being bound upon an entire generation of young Mongols is utterly excruciating and unacceptable.

Imagine, you cannot speak to your grandparents, spell their names, as your tongue cannot follow the highs and lows of the vast ranges of vowels and vocals, as mountains stretch across the horizon. Imagine, you cannot sing songs of praise in your mother tongue to express the beauty of those mountains in front of you. Imagine, you cannot access your own culture’s history, in your own language.

Cutting the tongue out is cutting the roots off, cutting the tongue out is severing you from your family, identity, culture and homeland. Without your tongue, something will feel forever lost. In the dark web of the unconscious, the dark place our memories of our ancestors are being forgotten, or waiting to be remembered again.

My own reality is testament to this deeply agonizing void, artificially created through generations of state-induced slow-violence overlapping with diasporic spheres of a multitude of narratives. I cannot speak to my ancestors, for I do not speak their tongue, and scarcely pick up a syllable or two that hint at a word that I barely may grasp. Our tongues are different, our mouths are incongruent. And I cannot avoid to wonder if it would be any different, if history would have not been so terrifyingly violent to our great-great-great-grandparents throughout the 20th century, the consequences still slowly, slowly simmering and surfacing. What would our homeland be like? What would our tongues and minds be like? Our tongues are becoming ghosts of what once was.

Inescapably, the brutal reality and (non)relationality to our collective heritage, Mongol bichig, written and oral, may still be in a deep slumber of the psyche somewhere. And as painful it may be to confront the violence-soaked history of Northern and Southern Mongolia, I believe it to be inevitable, in fact an imperative to reach a sustainable understanding not only for the future of our culture and people, but to also reclaim our collective heritage and history. If forgetting is a process, then remembering is as well. As tragic as it may be, in honour of our ancestors and the many Mongols that lost their lives and still are, I wish we can articulate resilience in response,34 once our eyes, minds and mouths open to the past and the very urgent present. May our tongues find the tones, high and low as the mountains and valleys of Mongolia. May our mouths find the flow of the rivers and trace the vastness of the steppe in our throats and lungs—and breathe.

NOTES

1 Ursula K. Le Guin, Earthsea: The First Four Books, 354

2 Nomin Zezegmaa,The Shamanic Gaze, Chapter: The Alchemist, Writing Without Writing, 121

3 Poem translated by Urgunge Onon in his translation of Chinggis Khan: The Golden History of the Mongols, xix

4 Jack Weatherford, Genghis Khan and the Quest for God, 93-94

2 Nomin Zezegmaa,The Shamanic Gaze, Chapter: The Alchemist, Writing Without Writing, 121

3 Poem translated by Urgunge Onon in his translation of Chinggis Khan: The Golden History of the Mongols, xix

4 Jack Weatherford, Genghis Khan and the Quest for God, 93-94

5 Personal correspondence with the artist Natalia Papaeva who embarked on the journey of learning Mongol bichig and her mother tongue Buryat and has kindly and generously shared her experience with me.

6 Prior to Cyrillic, the Latin alphabet was briefly introduced in the 1930s.

6 Prior to Cyrillic, the Latin alphabet was briefly introduced in the 1930s.

7 It perhaps was not ‘formally’ colonized in the sense of Soviet migrants settling in Mongolia. However from a fragment of my family history, I can trace severe colonial exploitation as tributary ‘payments’ were made to the Soviet Union in the form of livestock, especially horses. Each aimag, a total of 18 provinces, had to provide a thousands, millions of livestock who traveled the arduous distances to the Northern border where some of them nearly reached the gates of death instead of the grasp of the Soviets in Naushki. My grandfather was overseeing this entire process, and his main priority was the health and survival of the horses.

8 Manduhai Buyandelger, Tragic Spirits, 13

9 Ibid., 1; Nomin Zezegmaa, The Shamanic Gaze, Chapter: The Shaman, 92

10 Ibid., 71

11 Ibid., 71

12 Ibid.;81: “[...]If socialism had not collapsed, then without doubt the next generation would have faced obliteration of their ethnic identity and the end of shamanism and memories of the past.”

13 Manduhai Buyandelger, Tragic Spirits, 14

14 Ibid., 68

15 Rob Nixon, Slow-Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, 2013

16 Richard D.G. Irvine, Seeing Environmental Violence in Deep Time

17 Poem written by the Buryat artist Natalia Papaeva, 2018

Please see Appendix for more.

18 Manduhai Buyandelger, Tragic Spirits, 81

19 Ibid., 85

20 Nomin Zezegmaa, The Shamanic Gaze, Chapter: The Origin, 28; 34

8 Manduhai Buyandelger, Tragic Spirits, 13

9 Ibid., 1; Nomin Zezegmaa, The Shamanic Gaze, Chapter: The Shaman, 92

10 Ibid., 71

11 Ibid., 71

12 Ibid.;81: “[...]If socialism had not collapsed, then without doubt the next generation would have faced obliteration of their ethnic identity and the end of shamanism and memories of the past.”

13 Manduhai Buyandelger, Tragic Spirits, 14

14 Ibid., 68

15 Rob Nixon, Slow-Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, 2013

16 Richard D.G. Irvine, Seeing Environmental Violence in Deep Time

17 Poem written by the Buryat artist Natalia Papaeva, 2018

Please see Appendix for more.

18 Manduhai Buyandelger, Tragic Spirits, 81

19 Ibid., 85

20 Nomin Zezegmaa, The Shamanic Gaze, Chapter: The Origin, 28; 34

21 The diasporic movement of Mongols to Europe, as in my family’s case to Germany in the mid-late 20th century is a collective, conjuncational narrative shared

across the German-Mongolian diaspora.

22 The proper translations would navigate closer to the Mongol terms for the four directions of Northern, khoid or ard and Southern, umnu or urd.

23 Choghtuu Oghonos, Genocide on the Mongolian Steppe, xxxviii

24 Ibid.; xxxix: “In the seventeenth century, warriors from a group of nomadic hunters known as the Manchu emerged from the forests east of the Greater Hingaan Mountains. Mongolians accepted the supremacy of the newly rising Manchus over the grasslands and formed an alliance in 1635. The following year, Mongolians living south of the Gobi Desert joined the Manchus in a ceremony establishing the Qing state in the northeastern capital city of Mugden.”

25 What catalyzed this independence movement was the planned mass migration of Chinese peasants to Northern Mongolia supported by the Qing court which alarmed the Northern Mongolian nobles, clerics and commoners. Prior, the Qing strictly prohibited and forbade to cross and settle North of the Great Wall, as well as Chinese to Manchu / Mongol intermarriage.

26 Choghtuu Oghonos, Genocide on the Mongolian Steppe, xxv: “Chinese peasants joined the sect and rebelled against the Qing court. Society heads Yang Yuechun and Li Guozhen proclaimed themselves as ‘warriors to sweep the North,’ which translates to ‘warriors to wipe out the Mongolians in the North.’ Yang Yuechun and his followers used extremist slogans, including ‘kill the Mongolians and seize their land’ and ‘defeat the Qing and wipe out the Mongolians and Manchus’ [...] carried out large-scale massacres of Mongolians. The death toll may have reached tens of thousands. Tens of thousands escaped to the North, leaving their homes and lands behind.”

across the German-Mongolian diaspora.

22 The proper translations would navigate closer to the Mongol terms for the four directions of Northern, khoid or ard and Southern, umnu or urd.

23 Choghtuu Oghonos, Genocide on the Mongolian Steppe, xxxviii

24 Ibid.; xxxix: “In the seventeenth century, warriors from a group of nomadic hunters known as the Manchu emerged from the forests east of the Greater Hingaan Mountains. Mongolians accepted the supremacy of the newly rising Manchus over the grasslands and formed an alliance in 1635. The following year, Mongolians living south of the Gobi Desert joined the Manchus in a ceremony establishing the Qing state in the northeastern capital city of Mugden.”

25 What catalyzed this independence movement was the planned mass migration of Chinese peasants to Northern Mongolia supported by the Qing court which alarmed the Northern Mongolian nobles, clerics and commoners. Prior, the Qing strictly prohibited and forbade to cross and settle North of the Great Wall, as well as Chinese to Manchu / Mongol intermarriage.

26 Choghtuu Oghonos, Genocide on the Mongolian Steppe, xxv:

27 Ibid., xl

28 Ibid., xliii

29 Ibid., Translator’s Acknowledgement by Enghebatu Togochog

30 Ibid.

31 Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker, “Das ist unser Leben: Ohne Heimat, Land und Nahrung”;

trans.: “This is our life: Without homeland, land and sustenance”, 2015, 9

32 or ‘ecological recovery’, click here to see more.

28 Ibid., xliii

29 Ibid., Translator’s Acknowledgement by Enghebatu Togochog

30 Ibid.

31 Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker, “Das ist unser Leben: Ohne Heimat, Land und Nahrung”;

trans.: “This is our life: Without homeland, land and sustenance”, 2015, 9

32 or ‘ecological recovery’, click here to see more.

33 GfbV, “Das ist unser Leben: Ohne Heimat, Land und Nahrung”, 16-17

34 The country of Mongolia has set its goal on officially bringing back Mongol bichig by 2025, amidst the protests Mongols have in individual initiative started to re-learn or share their knowledge of the script as a political act of resilience. (+)

Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center

Manduhai Buyandelgerin

Tragic Spirits: Shamanism, Memory, and Gender in Contemporary Mongolia

(Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 2013)

Choghtuu Oghonos, trans. Enghebatu Togochog

Genocide on the Mongolian Steppe: First-hand Accounts of Genocide in Southern Mongolia During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Volume 1

(Leipzig: Xlibris, 2017)

Rob Nixon

Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor

(Cambridge, MA; London, UK: Harvard University Press, 2011)

Richard D.G. Irvine

Seeing Environmental Violence in Deep Time: Perspectives from Contemporary Mongolian Literature and Music

Urgunge Onon

Chinggis Khan: The Golden History of the Mongols

(London: The Folio Society, 1993)

Martha Avery

Women of Mongolia

(Boulder, CO: Asian Art & Archaeology / Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1996)

Jack Weatherford

Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World

(New York: Broadway Books, 2004)

The Secret History of the Mongol Queens

(New York: Broadway Books, 2010)

Genghis Khan and the Quest for God

(New York: Penguin Books, 2016)

Sarangerel Odigon

Riding Windhorses

(Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books, 2000)

Chosen by the Spirits

(Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books, 2001)

Edwin O. Reischauer & John K. Fairbank

East Asia: The Great Tradition

(Boston, Tokyo: Houghton Mifflin & Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1969)

Hermione Spriggs (et.al)

Five Heads (Tavan Tolgoi) Art, Anthropology and Mongol Futurism

(Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2018)

Manduhai Buyandelgerin

Tragic Spirits: Shamanism, Memory, and Gender in Contemporary Mongolia

(Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 2013)

Choghtuu Oghonos, trans. Enghebatu Togochog

Genocide on the Mongolian Steppe: First-hand Accounts of Genocide in Southern Mongolia During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Volume 1

(Leipzig: Xlibris, 2017)

Rob Nixon

Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor

(Cambridge, MA; London, UK: Harvard University Press, 2011)

Richard D.G. Irvine

Seeing Environmental Violence in Deep Time: Perspectives from Contemporary Mongolian Literature and Music

Urgunge Onon

Chinggis Khan: The Golden History of the Mongols

(London: The Folio Society, 1993)

Martha Avery

Women of Mongolia

(Boulder, CO: Asian Art & Archaeology / Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1996)

Jack Weatherford

Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World

(New York: Broadway Books, 2004)

The Secret History of the Mongol Queens

(New York: Broadway Books, 2010)

Genghis Khan and the Quest for God

(New York: Penguin Books, 2016)

Sarangerel Odigon

Riding Windhorses

(Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books, 2000)

Chosen by the Spirits

(Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books, 2001)

Edwin O. Reischauer & John K. Fairbank

East Asia: The Great Tradition

(Boston, Tokyo: Houghton Mifflin & Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1969)

Hermione Spriggs (et.al)

Five Heads (Tavan Tolgoi) Art, Anthropology and Mongol Futurism

(Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2018)

published as part of the exhibition:

Ripped out Tongues

30 APRIL - 09 MAY 2021

as part of the Window Project at Prenzlauer Studio

Berlin, Germany

Ripped out Tongues

30 APRIL - 09 MAY 2021

as part of the Window Project at Prenzlauer Studio

Berlin, Germany

Cyrillic Mongolian

Classical Mongolian

translations following soon!

Special thanks to:

Natalia Papaeva, Enghebatu Togochog, Jana Francke, Zezegmaa Zedendorsch

Natalia Papaeva, Enghebatu Togochog, Jana Francke, Zezegmaa Zedendorsch